– Good morning Bog-Hubert! You look a bit worried today — what’s the trouble? Need some coffee?

– Ah Vodçek, yes, thanks. Trouble? No, but I’m wondering about Abbé Boulah. Haven’t seen him for several days, — have you?

– He was in here briefly yesterday, mumbled something about a letter he’s working on — some question an acquaintance from the old days sent him, that he got all entangled in trying to answer.

– Sounds intriguing. What was the question, did he say?

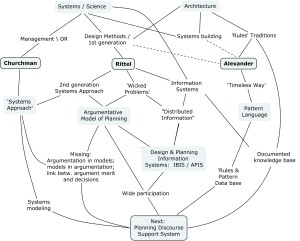

– As far as I could tell, it was something about the Pattern Language, the Systems Approach, and the Argumentative Model of Planning. Somewhat disparate issues, if you ask me, but I was busy with some weekenders here, didn’t get the whole story. Did you get a better sense of what that was about, Professor Balthus?

– Not sure. I think it was a question about reconciling the work of the three authors of those concepts: Christopher Alexander, West Churchman and Horst Rittel, who were all teaching at Berkeley in the sixties and seventies, and each made some important contributions to their respective disciplines.

– Yes, I remember: Alexander’s Pattern Language for Environmental Design; Rittel’s Wicked Problems and Argumentative Model of Planning and information systems. They were both teaching at the College of Environmental Design. But Churchman was in the Business School, working on his Systems Approach books and research, wasn’t he? So somebody wants to reconcile those different perspectives? For what purpose? Isn’t that a bit of old history? Haven’t all those disciplines evolved into new conundrums by now?

– Abbé Boulah didn’t explain the purpose of that question, Bog Hubert. But it’s interesting to speculate about it — you said it: conundrums. It seems all those disciplines are still facing challenges that suggest they haven’t solved their problems yet. And that the problems are more pervasive and general than we all thought at the time? So they were just looking at different parts of the problems at the time?

– That makes sense: I hear many people who call themselves systems thinkers talk about the need for a more holistic perspective: looking at the ‘whole system’.

– I’ve heard those folks talk too, Vodçek, and admired your patience with all that talk.

– Ah Bog-Hubert, and I have to thank you for not starting a brawl on some occasions — I’ve seen you get quite steamed up about what I guess you consider their still so limited perspective of their whole system? So you think there isn’t much hope for reconciling those perspectives?

– Wait, Vodçek. Before we get into that reconciling issue: what is your beef with the Systems Thinkers perspective, Bog-Hubert?

– Well, I think there are two main concerns I have, maybe there are two different kinds of those SThinkers. Sorry Vodçek, don’t throw that washcloth at me, I know you don’t like frivolous characterizations of your customers. Okay. Systems Thinkers.

One concern is that they still don’t acknowledge different opinions about their assumptions in the systems models; arguments. The models all look like any questions or disagreements about the model assumptions have all been settled, when they only express the model-builder’s view.

The other is the ‘holistic’ claim — the intent I don’t argue with, in principle, mind you. But to me, it seems to often focus exclusively on what they call the ‘common awareness, the unified ethical mindset they are advocating. But I guess that’s something that will come up if you really want to get into that reconciliation issue here…

– Okay, I’ll take your word for that, for now, though I think that’s a special group within the ST community that’s not shared by everybody. You don’t sound very optimistic about the prospect of reconciliation though? If ‘reconciliation’ is the proper word for what the question is after?

– Well, let’s just say I reserve judgment about that. I remember how Alexander pulled that dramatic break with the Design Methods group and I guess the Systems perspective associated with that — in the early 70’s when he first launched his Pattern Language. It seemed pretty irreparable at the time.

– Wasn’t he originally a key member of that design methods movement?

– Yes, Vodçek. But he got so disenchanted with what the various efforts of applying the tools of Operations Research and Systems technology, Building Systems in the Architecture realm — were doing to the built environment that he felt an entirely new direction and perspective was called for. And a lot of people felt the same way. There were aspects of what he called ‘quality’ missing that needed to be articulated and re-introduced into the practice and of architecture and urban design, that the systems view of that time didn’t seem capable of acknowledging. And there’s no question that the Pattern Language added many valuable insights about building.

– Well, didn’t Churchman’s take on the Systems Approach add a lot of similar aspects to the discussion that were not — and I guess are still not really — part of the general systems perspective?

– You are talking about all the components of his systems definition — the purpose, the designer, the decision-maker, the client, the ‘Guarantor Of Decisions’ (GOD?) the measures of performance for each of those parties? Yes, compared to some ‘definitions’ of systems expressed even today — ‘a systems is a set of related components whose relationships exhibit at least two loops’ is one I seem to have read recently somewhere — this view was certainly advancing significantly away from the early functional system concepts. What Rittel called the ‘first generation’ systems approach. It just seems that it was too abstract and general for environmental designers to work into their view of what they were doing. The Pattern Language was much closer to what designers in architecture, say, were already used to.

– I don’t understand. There are many architects who have never heard of the Pattern Language, and don’t seem to even want to get into and use these ideas?

– You are right. But consider: Architecture is a discipline that is already dominated to a large extent by — I hesitate to say, but the closest term I can come up with is ‘rules’. Patterns. The oldest ‘textbook’ on architecture (Vitruvius) talks about ‘orders’ which are rules for the parts and design of buildings. For centuries, there were design guides that were essentially ‘pattern’ catalogs. There are client requirements and expectations, constraints by climate, culture, available building materials, the knowledge and ‘ways we’ve always done it’ of all the trades involved in building construction all the building regulations. All those rules are giving you quite a range of options for how to put buildings together, sure — but they all say simply: Follow the rules, meet the requirements, and you’ll get the client’s go-ahead and the building permit. I’m not saying that is easy, and it definitely takes skill and creativity to come up with new, inspiring, innovative designs juggling all those rules and expectations. But in the end, the act of having followed the rules ‘guarantees’ the result.

– Some guarantees: all the ugly buildings that have gotten permits?

– Yes, Alexander was quite right in pointing out that all those rules did not guarantee quality environments — that in fact the rules, including the systems concerns — which in the building realm manifested themselves in ‘systems building’ or ‘industrialized building’: standardization, dimensional coordination, mass production of parts and mechanized assembly — all tended to produce deadening, uninspiring environments without ‘quality’.

But look at what he added to fix that: the patterns too all look just like rules. Better rules, arguably — but rules all the same: In a given context, there exists a conflict or problem, and tho resolve or avoid it, here’s the general essence of the solution. The patterns are related in certain ways — and all give the designer quite a range of options — Alexander’s claim was essentially that ‘you can do it a thousand different ways and never end up with the same result twice’ — but you have to follow the essential pattern rule. If you don’t, you’re not solving the problem.

And this is what enables him to reject all the measure of performance and evaluation procedures of the design method and systems movement: the result is guaranteed by virtue of having followed the rules: no evaluation needed.

– I see: the design methods efforts, the systems modeling were essentially incompatible with Alexander’s ‘Timeless Way of Building’ and Pattern Language from the outset. That explains your pessimism about reconciliation all right. But did that also ignore the aspects Churchman had added to the systems story?

– I agree there was a disconnect — but as you said, it wasn’t easy for architectural designers to adapt Churchman’s concepts in practice. It does explain why the Pattern Language became such a hit in quite different disciplines — software development, for example. It always surprised me; but now I understand: especially in the computer realm, the machine has to work according to rules, patterns, so software has to consist of valid rules.

– Right. But what about Rittel — he was coming from design, a systems view of design, as well, didn’t he? What made his work incompatible with the Pattern Language view?

– Good question. Though he was teaching design, at the Hochschule für Gestaltung, earlier, architecture and urban and regional development at Berkeley, his background was in mathematics, statistics, systems. And he was involved at that time, through a Systems Research think tank in Heidelberg, with the design of information systems for planning and design, even political decision-making.

He was looking less at the kinds of problems that the systems folks of the ‘first generation’ were adamant about ‘defining’ and stating clearly and succinctly at the outset of a problem-solving process, but at larger problems in society — problems like urban renewal, traffic, housing, education, the environment, — that early grand ‘expert model’-based solutions had not solved but actually made worse.

And his insight was that those problems could not be ‘defined and stated’ clearly — that there were widely different opinions about what causes them, how to describe them, and of course, what would qualify as a solution — in fact, that there were no clear and ‘true’ answers — ‘solutions’ for those problems he called ‘wicked problems’. Essentially, — among other properties of WP’s — he found that each WP is essentially unique, unprecedented in most respects. And that meant: there were no rules, no patterns, for dealing with them that ‘guaranteed’ the solution.

– Bummer. And clearly incompatible with the Pattern Language approach, even I can see that. So what was his answer to that Wicked Problem?

– Put very briefly: the Argumentative Model of Planning. He saw the design and panning activities as a process of raising and answering questions — about the problem, understanding it, the way it affects different people, and about what would qualify as a solution. A discourse. The process, and the information system needed to support it would have to acknowledge the contradictions in the discourse — the proverbial ‘pros and cons’ about proposed solutions.

It would have to accommodate wide participation — the information about how the WP affects people in the population is ‘distributed’, not dealt with either in the expert’s education or in neatly documented traditional information systems — after all, it’s ‘unprecedented’. So he started to develop ‘Issue Based Information systems’ (IBIS) and ‘Argumentative Planning Information Systems’ (APIS) — and — less well documented — the principle of ‘complicity planning’ — where decisions were based on — informed by — the merit of arguments brought forward during the discourse but carried by all participants’ willingness to assume responsibility for the decisions and the risks associated with their eventual consequences.

– Hmm. If I understand this correctly, this was an evolution or change of direction of the systems perspective — and as such conceptually compatible with Churchman’s view of systems. Is that a reasonable way of looking at it? So why wasn’t it adopted by the wider systems thinking community?

– Ah, now we are trying to find an answer to Abbé Boulah’s question, eh?

– Not so fast: I’m not sure we are anywhere close to that, Vodçek.

– Why? What would it take to reconcile these perspectives? I see different kinds of problem situations to which the approaches apply; so each kind of situation needs to be dealt with by the appropriate approach. Isn’t the difficulty just in making those distinctions?

– It isn’t that simple, Vodçek. The situations and approaches aren’t that clearly distinguished so everybody can quickly decide ”Ah, this is a WP, let’s use the Argumentative Model” as opposed to “Here, we have a clear conventional design problem to which all the established rules apply; so let’s study the rules and the patterns and use them to develop a solution.” And “This one is a typical systems modeling challenge — many variables, related by many feedback loops, but we can model it and predict its behavior, to select the intervention with the optimal outcome.” The wicked questions crop up in the middle of the apparently most standard modeling efforts. The implementation of even the boldest innovative plans involve many conventional ‘patterns’ and requirements.

But you could say that the fallacies and flaws of all three perspectives can be traced to a tendency of selective reliance on selected aspects of their respective model.

– Can you explain that, Professor? I’m not sure I understand that one.

– I’ll try, Vodçek. Take the reliance of the systems folks on digitized data bases. Large scale planning depends on data. And the tendency is increasingly on using sophisticated computer programs to actually draw inferences — statistical and logical — from the data. That must rely on the assumption that the data are actually ‘correct’ — ‘true’ and thus reliable. Not only that the measurements are accurate, but also that the variables that are measured are appropriate. And for the logical part: that the data are consistent, not contradictory. If there are contradictions, no reliable conclusions can be drawn. So there is an upfront effort involved in setting up and maintaining the data base to remain contradiction-free. The science basis of the data — observation, measurement, testing, etc. tries to ensure that: understanding a situation as it exists — the aim of systems thinking: to understand the ‘whole system’ — aims at getting the ‘true’ story about the problem.

But now look at the planning discourse. It consists of a lot of ‘pros and cons’ — which are contradictory claims. If a data base aims at properly representing a planning discourse, shouldn’t it accommodate those contradictions?

– Well, you could say that it’s the precisely the purpose of the discourse — with participants presenting evidence to support their claims — to develop what we’d call the ‘true’ picture of the situation, the ‘correct’ problem understanding.

– Yes, Bog-Hubert. But in reality, that isn’t as easy as it’s said. And as long as it’s not settled, if it ever can be, the data base for planning and policy-making contains contradictions, and the expert system that can draw reliable conclusions from it is out. Pipe dream. Even for factual claims and about what works and what doesn’t work to achieve a desired outcome. But there — I said it — it’s the desired outcome that we argue about most intensely — and the labels ‘true’ or ‘false’ don’t apply to those claims. So the data base can’t be consistent by definition. Which means that a lot of the sophisticated tools used in systems modeling simply don’t apply to the planning discourse — even the most trivial ones.

– Hold on, I’ve got to think about that for a moment.

– Okay. Let’s take a break. Perhaps Vodçek can draw a map of our discussion in the mean time?

***

– Ah, I see.

– Well, it’s just the overall topics so far. I thought we’d use the different purposes of the three approaches as the basis for looking for compatible or incompatible features.

– What do you mean?

– Well, look at Churchman’s work. Or the systems perspective in general. Could we say that the purpose of those kinds of studies is mainly to understand the systems we are dealing with, and how they behave? And the understanding would also mean to be able to predict how the system would behave when it is affected by this or that intervention, which is how the systems guys talk about design or planning proposals. So any planners would have to deal with those questions whether dealing with a ‘wicked’ problem or a ‘tame’ one, wouldn’t they? And that is also the basis on which a pattern is developed and adopted — if it wants to have any claim to validity. So there’s a first set of compatible aspects. Couldn’t we find more of those?

– I suspect we can find as many common features as we can find further incompatible characteristics. For example, the fact we mentioned earlier, that systems models seem systematically eliminate any semblance of arguments or difference of opinion about the assumptions in the system — variables, values, relationships — which therefore always turn out to represent the modeler’s understanding of the problem to the exclusion of other views. And that the arguments in the Argumentative model seem to always just describe one variable’s relationship to another — the network of arguments has considerable trouble coming to grips with the many relationships and loops in such a system — are those just temporary incomplete aspects of these approaches or fundamental differences?

– Hmm. What about the movement that claims to be seeking better awareness and understanding of the ‘whole’ system — still claiming to be part of the systems thinking tribe — but what it comes to suggesting what to do about solutions to the big problems and crises, seem to focus on achieving a common, even ‘universal’ kind of ethics and morality, that will determine the decisions?

– Good point — I had forgotten about that aspect of the systems movement. I think that is one of the basic flaws of the way these tools are used.

– Huh? Please explain: basic flaws?

– Let me see. Perhaps I’ll use the structure of the ‘standard planning argument’ to explain that. We talked about the fact that the basic planning argument of a plan proposal A has two or three key premises: To support the proposal:

“A ought to be adopted” the premises used are:

1) If we implement A, result B will happen, — given certain conditions C;

and

2) Result B ought to be pursued (is desirable);

and

3) Conditions C are present.

Of course planning decisions always rest on a number of such arguments, never a single one. But here my point is: Most of the time, people don’t explicitly state all the premises but only one or two, taking the other premises ‘for granted’ — which means that the discussion isn’t likely to focus on those. This allows us to distinguish between some major ‘movements’ or tribes that rely on only one of these key premise types to support their case: Look at what happens when people stress and rely only on the first premise to make their case:

– There are the ‘engineers’ who have found a way of realizing the If A then B relationship or technology: simplified (unfairly of course): “we should do A because we can, to get B”. Technicians, causal analysis types — remove the cause, never mind any consequences of how you do it…

– Or look at resting the argument on the second premise: there is the philosophy of ‘B is the goal’ we should all support, by all means — and the effort of many such groups is aiming for evoking the common awareness and adoption of universal goals (sustainability, global piece, or ‘creativity’ or change, innovation) — at all costs.

– And finally there is the group relying on the third premise, which has to do with data, or increasingly BIG DATA — the conditions of the system overall: “The conditions for implementing plan A are given”. As if the decisions flow logically from those data.

I know I’m drawing caricatures here — but you’re not laughing: it’s true, isn’t it?

– Hmm. Coming to think of it, there are countless management consulting ‘brands’ of ST approaches that fall in one or the other of your three categories. You might want to add the ‘user design’ movement — the people who proclaim that whatever a cooperative bunch of people are ‘co-creating’ will be good: the solution will ’emerge’ and be ‘good’ just because it’s co-created. Of course, they might need a consultant ‘facilitator’ …

– Oh, many people are being more straightforward than that, bluntly calling for the strong leader — sometimes with a sly suggestion that they might just be that leader — well so far, perhaps just ‘thought-leader’ — who will unify the will of the people, precipitating the needed change from which the ‘new system’ will emerge, that just can’t be described yet because it must ’emerge’.

– You are scaring us here, Vodçek. Are you trying to get us to invest in some liquid courage medication?

– Well, relieve our concerns, Bog-Hubert. What would you suggest Abbé Boulah might write in his reply to this wicked question?

– Oh — why me, why should I make a fool of myself? You go first, Professor!

– Chicken. Well, for starters, without trying for a clear answer to the original question itself: can we say that there should be some ‘system’ in place that could be activated as needed — when a problem arises that needs some form of collective action. A system that can alert people when there is such a need — and then is open to all kinds of questions, ideas and answer and argument contributions, by anybody. To start and support a public planning discourse. We discussed before some aspects of what such a planning discourse support system should be like. For example, that it should have a provision for assessing the merit of contributions, the plausibility of arguments — by all participants. And a mechanism for making the connection between that merit and the eventual decision clear and transparent, if not outright determining the decision. So that aspect would clearly be drawing on the argumentative model of design — Rittel.

– I see where you are going here. The system should then also provide or contain access to what we might call the ‘rules’ applicable to the domain of the problem — drawing on past experience, laws and regulations, the scientific-technical knowledge applicable to that domain — as well as ‘patterns. They will become part of the argument set for the detailed description and refinement of the plan.

– Yes — and both the discussion and the ‘documented’ data and reference base will also be the basis for the development of system models of the situation — to support the ‘understanding the situation’ part of the process.

– Good point, Professor. yes. Of course there are some significant pieces of work that need to be taken up before such a system can be put to work.

– What are those, Bog-Hubert?

– They have to do with the issues we mentioned. The relationship between the systems models and argumentation: better integration of model insights and displays into the argumentative process on the one hand, and acknowledgement and accommodation of argumentation — differences of opinion — about assumptions of the systems models.

– I am worried about the final part of that system, — I can see how participants can develop their individual measure of plausibility for or against a plan proposal — we have talked about some work for that aspect. But then: if many participants come up with reasoned plausibility measures that differ significantly from one another — how can that be translated into a collective decision? Just voting it up or down isn’t the answer — it will destroy the link between the merit of the information and the decision, and thus be open to hidden agenda influences and similar problems.

– Yes — violating the principle that the voting minority shouldn’t just be on the losing end of the process. And any calculation of a group plausibility measure from the individual values has problems. The attempt by the unified values people amounts to sidestepping this problem, believing that if science can clarify the facts, the only problem is to make sure we all share the same opinions about what we ought to do and the values we ought to pursue. And while it sounds so well-intentioned and beneficial, that is even more scary than the prospect of having a messy system of haggling our dirty compromises between different parties with different views of what we ought to do…

– And you hope that Abbé Boulah will have a better answer for that than what we have been bouncing around here?

– We might have to help him out with that when he shows up…

– He better show up, soon? Or this might drive a fellow to drink…

– Cheers.

2 Responses to “Alexander, Churchman, Rittel: A Fog Island Tavern Conversation”