Morning in the Fog Island Tavern. Tavern keeper Vodçek getting worried about one of his usual customers.

– Hey Bog-Hubert, what’s eating you? All morning you’ve been sitting there shaking your head over your tablet, even letting your coffee get cold? Am I going to have to start a no-internet rule in this lowly bistro? Here’s a warm-up. Care to share your gripes?

– Thanks Vodçek. Yes, it’s frustrating. All this unsocial talk by social networks do-gooders and holistrolls, systems Sthinkers and BigDataMongers, about how to save the world…

– Huh? Holistrolls? Sthinkers?

– Sorry, Renfroe. I’m talking about those fervent advocates of holistic thinking — Holist-rollers — morphing into trolls that obfuscate discussions by calling every idea they don’t like ‘linear’ or ‘reductionist’ …

– Good grief, are you giving us an explanation or an example of that kind of talk?

– Good point, Renfroe. Bog-Hubert, is your creative spirit morphing you into the very kind of name-calling troll we have heard you ranting about before?

– Name-calling, Abbé Boulah? Well, I call it calling a spade a spade. But yes, I guess it’s not any more conducive to constructive dialogue than their rehashing their principles and mantras without really getting off the starting plate.

– Well, what’s the race about, then, perhaps we can get moving?

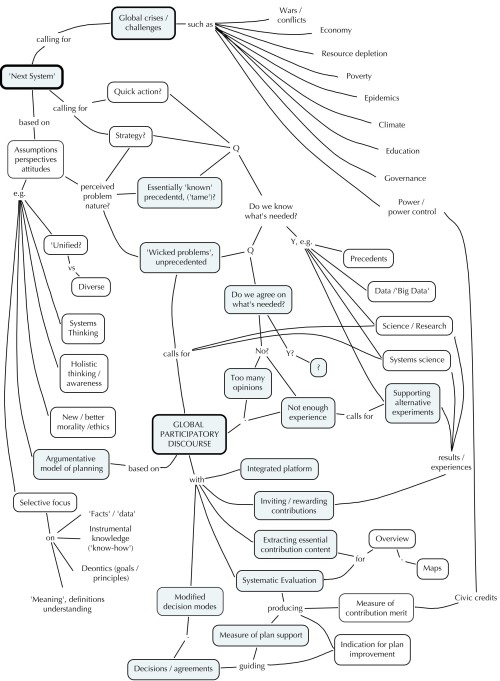

– Short story, it’s about the strategy for tackling the big crises and challenges we are facing. By ‘we’, they are referring to humanity as a whole. And all those groups calling for a ‘new system’ to replace the old one, to fix things.

– Wait, Bog-Hubert: what ‘system’ are they talking about?

– Oh, it’s just about everything, — the economy, politics and governance, education, justice, religion, morality, production and consumption, information, trade, sustainability, research, climate change…

– Well, don’t they have a point saying that those systems don’t seem to work anymore, if they ever really did, and something needs to be done about that? At least thinking and talking about what a different order of things should be like?

– Sure, Vodçek. Talking, discussing it would be good — if the discussion could be organized in a more constructive fashion. But I am getting tired and suspicious of all those calls for a ‘new system’ to replace the ‘old one’ — calls for adopting this or that mantra wholesale as a guiding principle, but not getting into details about what kind of destruction and upheaval would be needed to ‘replace’ the old system, and how to deal with all the competing ideas out there about what that new system should be like. Let alone how to go about achieving it. Blindly proposing tactics, tools that simply don’t fit the nature of the problems involved.

– If you would explain that so we can understand what you are talking about, I’ll buy you another coffee…

– Okay: Take the lack of distinction between the nature of the problems we are facing. For some people, they — or some of them –are seen as problems we have dealt with before, for which there are precedents, tried-and-true tools, methods and approaches, laws — both natural and man-made, regulations, data about people’s habits, expectations and needs. Experts who know about all that. So the task is — plausibly enough — to bring the relevant knowledge together, perhaps making needed adjustments and refinements to the tools and methods, eliminate errors, mistakes, corruption etc. in the present system. Science and systems thinking, bless heir hearts, working hard to contribute to better understanding of the situations and systems. Then of course, leadership is needed to implement the ‘correct’ solutions generated by all this data.

– Sure, as long as the leaders are advised by the systems consultants, eh? But okay, sounds reasonable enough. So?

– The other view is that these social planning problems are ‘wicked’ problems — as Rittel taught us — unprecedented, understood very differently by different people. The information about how the problems and proposed solutions affect different parties is ‘distributed’, that is, not in the experts’ textbooks. There are no ‘correct or ‘false’ solutions that can be tested — just good or bad, better or worse, perhaps even evil — and people’s judgments are very different about that. It’s worth studying the properties of these problems. And so on. Go back and read the old 1970’s article about the ten or so properties of wicked problems. It would keep those folks who are pushing yet another approach to ‘solve WP’s’ to be more careful with their promises. But even the lists of those properties in many publications have been watered down to sound more benign and manageable. Anybody promising tools to ‘solve’ wicked problems either doesn’t understand their wickedness, or is selling snake oil.

– So what do we need to cope with those nasty problems?

– Would I be sitting here shaking my head and letting my coffee get cold if I knew, Renfroe? There are a few major but different attitudes I see out there. Besides the snake oil promoters, that is. I see one cluster of groups who seem to believe that the main missing remedy is a fundamental change in people’s awareness, attitudes, understanding of the ‘whole system’ — moral principles, empathy, beliefs.

– ‘Unifying’ beliefs — the ones that are supposed to prevent conflicts, wars, corruption, inequality and injustice, once everybody has come to accept those same principles and unified mindset — wouldn’t you add those?

– Ah Vodçek: I think I see what you are worried about — and isn’t that your concern as well, Bog-Hubert? The danger of falling into the trap of generating a mindset approaching totalitarian dominance? Not by brute force but by social, psychological pressure…but equally deadening.

– It’s difficult to argue with all the goodness faith articles of those movements, yes. Isn’t it reasonable to assume that the responses to the crises must be somewhat coherent, consistent and, yes, have a common unified basis? Otherwise, there’s a danger that inconsistent, incompatible actions will make things even worse. And it feels unfair to disparage their good intentions as ‘totalitarian’ or ‘fascist’ — which is a different way of saying ‘unified’. But I agree, as far as I can see, they don’t usually provide enough information about how a ‘new system’ would deal with people who are not entirely converted to the faith.

– Yes: or people who even attempt to give meaning to their lives by ‘making a difference’ that includes differences with the prevailing unifying principles?

– We’ll have to discuss that problem in some more detail, I guess: put it on the list. But what was the other attitude you mentioned, Abbé Boulah?

– Ah. Thanks for reminding me, Vodçek. Well, in order to develop and then convince people about plans for collective responses to challenges — crises, or desires for new and better system — that meet the criterion of being sufficiently acceptable to all affected parties —

– Why does it have to be acceptable to all — isn’t the democratic principle that we discuss a plan but then vote on it, letting the majority decide what’s to be done? Not sure ‘decided by majority vote is really equivalent to ‘acceptable by all? Or are you going to toss that principle too in your new plan? Sorry for interrupting…

– You’re forgiven this time, my friend, because the point you are making is an important one. The much touted democratic principle, the core of democracy and freedom: ‘free elections’ but decided on the majority rule — isn’t that just ensuring that the ‘losing’ parties will harbor resentments, arguably insist that the problems the plan was supposed to solve haven’t been solved at all, just shifted around, to be suffered by different folks?

– Why is that?

– Because, Renfroe, the majority rule decision principle may assume that the arguments of the losing minority aren’t plausible or convincing enough to persuade the winning majority — but says nothing about the majority’s arguments having convinced and persuaded the minority. Or about giving ‘due consideration’ to their concerns. The issues may not have been resolved at all, just wiped off the table. The concerns and arguments that the democratic discourse is supposed to bring out for ‘due consideration’, for ‘weighing the pros and cons’, may be totally ignored by that decision rule. Leaving the problems to fester and grow. But isn’t that one of the issues we have to take up later, Bog-Hubert? You think the current forms of discourse wouldn’t be up to the task even if people were willing to do better?

– Yes, I think the first task we have to face is the organization of the discourse. It is supposed to facilitate wide participation, to bring in the arguments. To include the careful evaluation of their merit. Does it do that? And most importantly, to connect the decisions transparently and responsibly to the merit of the arguments and concerns?

– Why discourse? If we recognize dangers, shouldn’t we focus on doing something? Actions?

– You’d be right if we knew and agreed on what the right actions are. But what we see is that we don’t agree, and I think it’s fair to say that ‘we’, the humanity overall, just don’t yet know what we ought to do? So we may need more research, more experiments, and bring the results into a discourse designed for leading to better decisions?

– And you are saying that current forms and formats of discourse don’t do that properly? Are you going to tell people how to discuss and argue their issues?

– Good heavens, Vodçek, no. Sure, given all the recipes of the disciplines that tell us how to think right, the ‘rules of order’, the textbooks about how to persuade people, your suspicion is justified. I’d add to that concern the various efforts to introduce different forms of expressing the concerns — languages, codes — perhaps to make it easier for machines to document and analyze the discourse. As if the discussions weren’t already full of different disciplinary jargons that make the content difficult to understand for lay folks. I don’t think that’s what is needed. Isn’t it more a matter of displaying the essence of the different contributions? For overview, comparison, and evaluation? In common conversational terms?

– All right. So the problem is the design of the discourse platform and its support system. Aren’t there already a lot of programs and systems and social networks on the market that do exactly that? Using the new communication technology devices and the internet, that allow virtually everybody to talk to everybody else? I can’t keep up with them all — aren’t they making progress?

– Yes. They are amazing, interesting, fascinating, some people even say: addictive. But have you tried to find out which one you’d use to actually carry out a real public discourse about an important issue? Tried to follow one of those discussions to help you make up your mind about what side you are going to support, maybe even to contribute your efforts to?

– You mean sending in the donations they are all asking for isn’t enough, Vodçek?

– Phht. Do those groups ask you about your opinion or ideas? I’m not talking about the mere ‘discussion’ networks that make their money by selling ads, where people go for endless exchanges of mostly posts that immediately divert from the questions asked, but where there is never any real effort to reach a conclusion or decision. The groups that are actually trying to do something have pretty much made up their minds, their proposals, and just want your money to help promoting them. Don’t confuse them with any questions or different ideas…

– You’re right, that scene is good evidence that we need a more effective public discourse platform. One where people can bring in their ideas, concerns, their arguments, but don’t need a lot of money for spreading their message, for advertising, and lobbying the folks who really make the decisions. One where people can bring up their different views about those issues, look at others’ ideas, think about them, maybe contribute to modifying plan proposals in response to others’ concerns.

– What about those people who are claiming that instead of throwing their views, their thinking about what we ought to do at each other, everybody should just do the ‘right thing’, not what they think is the right thing? Focus on what actually is the case, not what they think is the case?

– Oh, Sophie, you mean that fellow on the internet you were so annoyed about, what was his name? I know those types. Are they just trying to tell everybody else they are wrong, stupid or tied up and blinded by their ideologies (which are also wrong, of course) — trying to get everybody to accept their version of what is happening and what ought to be done? Or do they actually have a better access to the right thing?

– Hard to tell. I mean, of course we should base our thinking on the actual facts — on reality — and our proposals about what to do on what is the right thing to do. Can’t argue with that; it’s barging in open doors. No, I get confused about that thinking part: Say I have actually found out what is really happening, after having changed my initial flawed assumptions, doing some investigation, which in part consisted of listening to what other folks were thinking (but who were of course wrong because they were just thinking, not knowing, according to that fellow) — am I not still just thinking that I know, and therefore still wrong?

– Could be that they were just hoping you’d accept some story from some authority or holy book — on faith, not thinking, mind you? But then: what if there are several wise guys or holy books around, that tell you different stories…

– Well, Sophie, I’d say forget those disruptions. Ignore them. Look, we are all trying to engage in a discourse where different views about what is the case, and what ought to be done, are put forward for examination — the discourse ought to report and be tied in with actual observation, measurement, experiments. So aren’t we actually already doing that: finding out, to be best of our current information and data — what the real facts are, what is the right thing we ought to do? Or has this guy you mentioned suggested something better?

– Good point, Bog-Hubert. But don’t offend them by too obviously ignoring them; They’ll just go around claiming you refuse to accept reality and the right thing to do.

– ‘The right thing to do’, Vodçek — isn’t that just another way of saying ‘what we ought to do’? Repeating a proposed position — by without giving a reason why something is or isn’t the right thing?

– All right, you are getting to the core of problems here. I’d say we should be more careful and humble with those terms: ‘reality’ and ‘the right thing to do’. Do we really ever know reality? I think Karl Popper’s warning about the ‘symmetry of ignorance’ is a good thing to keep in mind: (I forgot the exact place) — What I know — a — about reality (even about the situation involving a problem we are facing, and all its relations with the rest of the world) and what you know — b — amounts to precious little compared with the infinity of what there is to know: a/∞ = b/∞ = 0. Zero.

– You are not inspiring a particularly optimistic outlook here today, my friend. What are we to make of that, eh? Chastise you for spreading views not conducive to increasing the self-confidence of would-be world saviors? Bad boy. Almost as evil as using the term ‘argument’ in polite discourse?

– So sorry. Yes, your statement ‘to the best of our current information’ is more appropriate to keep us more modest: We find that we have to do something, but we know that our big data information is limited, our knowledge imperfect; we can’t be completely certain about anything.

– So we can’t do anything? Give up?

– No, Renfroe: we have to take a chance, assume the risk of possibly being wrong. And if we can’t assume that responsibility by ourselves — even those of us who are making plans and decisions on behalf of others and the public — we need to find people who are willing to share that responsibility, share the risks.

– That’s what Rittel called the ‘complicity model of planning’, didn’t he?

– Right, Bog-Hubert.

– So now we have to deal with the issue of responsibility and accountability as well. What does that actually mean — other than pompous words by leaders who are always letting others suffer the consequences of their irresponsible actions?

– Put that one on the list too, for now. We haven’t gotten very far with the design of the discourse and its support system yet. Shouldn’t we get some more detail on that first?

– Okay. The insight about the missing reasons why, in those exhortations about doing the right thing, that was the next step there: the arguments, pros and cons about plan proposals.

– Oh, great. Are you going to dump the entire literature on argumentation, from Aristotle on through two thousand years of logic and critical thinking fat books on us here?

– We’d deplete Vodçek’s supplies of coffee and other inspiring lubrications if we tried; no. I don’t think the discourse framework has any business telling people how to think and argue — that’s somebody else’s job description. Education? Regular columns in the newspapers? Fact-and fallacy-checking internet sites? Interesting possibilities there, whole new industries? No: the first task of the discourse platform is simply to alert people about what plans and policies are being proposed, to then encourage and invite comments, arguments, ideas, and to record them for reference.

– I’d say we have achieved that step already. And it isn’t a pretty picture, if you ask me. Or don’t you suffer from that information overload like the rest of us, Abbé Boulah?

– Oh, I do, sure. The avalanche of so-called information, data, opinions, arguments that aren’t really coherent arguments but rants and quarrels replete with repetitions and name-calling — quarrgument would be a better name — that our glorious information technology has let loose upon humanity. It’s like one of the curses of ol’ Pandora’s lacquered box. Enough to make one lose faith in the species. That’s where the next task of the discourse platform is so desperately needed: to extract the essential core of all the discourse contributions, — especially the essential argument core of all those pros and cons — and to display those in a concise, condensed form so people can keep a clear overview of the key subject matter. And also to make it easy for them to form reasonable judgments to support or reject the plan proposals. That’s where a lot of work is needed.

– I thought your buddy up at the university has done some useful work on that part?

– Well, yes, but it’s work in progress, and he’s retired, and doesn’t have the means nor the institutional support to conduct substantial case studies, experiments and tests of his ideas any more. So it’s slow going.

– Why, aren’t there other researchers to take up that work?

– Looks like he’s not doing enough to spread the work, to get others interested and involved, to market his ideas. He seems to think it’s enough to have thought them up and written some books and papers about them.

– Lazy, eh?

– Well, Sophie, he probably wouldn’t argue with that uncharitable assessment. But he does keep working on all this — he’s actually written more since he retired than he ever did while teaching. So is that really a fair assessment? And there’s the problem that those ideas are crossing several academic discipline borders, each of which is saying that the questions are too far out of their domain, or if they aren’t, what does that guy from the other department know about their science? Besides: why does somebody who can think up useful ideas and methods also have to be the slick salesman to sell them to the world? But perhaps we have to be patient, and wait for other people to come up with better ideas… For now, I’d say we do have some basic concepts that could be put to good use for that second step.

– So what more do we need?

– The next task may be even more important. All the contributions to the discourse, even in some cleaned-up, organized and concise display, don’t yet make it clear how they support the decisions we have to make. Especially because — by definition — the ‘pros’ are contradicting the ‘con’s, and not all arguments supporting the same position carry the same weight. That needs to be sorted out and clarified: evaluation.

– What’s the purpose of that? I mean, people are usually voting their preconceived positions anyway. Or the managers, leaders, governors or presidents are making their decisions whether or not they have really ‘carefully weighed the pros and cons’ like they promised in their campaigns…

– Well, isn’t that precisely the problem? Actually, I thought you were going to bring up the argument that if we follow the steps of some approved approach — something like the Pattern Language, the fact of having followed those rules guarantee a good, valid solution: no evaluation needed, case closed. Which of course doesn’t apply to wicked, unprecedented problems for which there aren’t any established rule systems. But you are actually making the case for more careful assessment here, aren’t you?

– Next thing, you’re going to accuse me of speaking prose. But I still don’t see just what the benefit of such evaluation procedures is going to be.

– Actually, there are two different purposes a more systematic evaluation would serve. And I guess I should make it clear that it should be done by all the folks participating in the discourse, not by some separate panel of experts. And it should be detailed enough to address the individual premises or items of information in the discourse contributions, and their supporting evidence, if needed.

– Sounds like a lot of extra trouble. But go on…

– Yeah, You may have to decide in each case whether its’ worth preventing bad decisions. Then the first benefit is that the assessments can help us see where the actual disagreements are, so that the discussion can focus on clarifying the basis of those disagreements — misunderstanding, inadequate factual information, different goals and concerns? And doing so, help modify, improve the proposed plan to make them more acceptable to all parties.

– What do you mean — aren’t the disagreements obvious?

– Not always: You can be against somebody’s argument for a plan A that claims that A will lead to effect B (given conditions C), that B ought to be, and that conditions C are present. You may doubt the first premise that A will cause B. Or you may not agree that we ought to pursue B as a goal. Or you may agree with both of those, but don’t believe all the conditions C are in place to make it work. So just saying that you disagree might induce the proponent to cite all kinds of evidence and big data to support the claim that A will cause B, when it’s actually consequence B you disagree with…

– Okay, get it. And your second aspect?

– Right, getting to that: the benefit a more thorough evaluation could produce is a more specific measure of support of the proposed plans or policies, after all the talk has run its course.

– What good would that do? If people vote their preconceived solutions anyway?

– It could serve to introduce a greater degree of accountability into the decision process, don’t you see? It would make it more difficult for the decision-makers, whoever they are in each situation, to decide to adopt a plan that has achieved a very low or even negative approval rating from the discourse participants. Or conversely, reject a plan that has gotten a high degree of approval from the group.

– Would that be needed if the decision is based directly on that measure of approval, — if you can develop a reasonable measure for that, which remains to be clarified, because I’m not sure I can see it yet.

– Good question, Vodçek. Actually, several questions. Your main one: why not use the support measure as the decision criterion, like the outcome of a yes-or-no vote? It has to do with the question whether we can be sure all the information that should be given ‘due consideration’ is actually brought up and made explicit in the discussion, so that it can be included in the evaluation? Next: even for all the points that have been raised explicitly: how is that measure of support made up of all the judgments about individual answers, arguments and their premises, first for each individual participant? And finally: how would we construct a meaningful ‘group measure’ of support from all the individual judgments?

– A veritable nest of wicked questions in themselves — and you don’t have good, final answers yet?

– Right, sadly. To the best of our current view: we can’t guarantee that the explicit contributions actually represent all pertinent considerations that legitimately should influence decisions. Like some issues that are important but ‘taken for granted’ so nobody bothered to bring them up. Or somebody not disclosing information that could be detrimental to other groups. And for the other questions, there are several plausible answers or approaches to each of them; for example, how to construct group support measures from the individual judgments. And since we don’t have any experience with how they would be used in a real situation yet, none of them is a clear-cut solution for all situations. Those different situations, finally, may involve institutional traditions, constitutional constraints, the different ‘accountability’ status of the people making a recommendation versus those who have been appointed to make decisions and whose jobs depend on how they do that, etc. So in many situations, the actual decision may have to be made by traditional means and rules, and our support measures should be no more than guiding support information.

– I see. But if the consultants get hold of this, they’d mash it into some new ‘brand’ and sell it as the ultimate decision rules anyway…

– Now, now. Don’t throw all the consultants in the bathwater… The managers do need somebody to come in and tell the troops that the boss is right…

– Well who’s the cynic now? But aren’t we getting away from the main issue here, Bog-Hubert?

– Oh yes, I realize that: consulting for a company that is locked in fierce competition with other firms is somewhat different from calling for the grand new system for all mankind, where conflict and competition is supposed to be replaced by universal awareness, goodwill and cooperation. So the consultant’s systems work has to be different from the grand public system discourse, because they still have to accommodate competition as the essential business issue — but the stories for getting the team inside the company to work more productively are using the same kinds of mantras that apply to the grand system. Somebody might want to take a look at that discrepancy. Vodçek, you have some ideas about that?

– Yeah I have often wondered why they all have to come up with their own different ‘brand’ of systems thinking tools until I realized that they can’t really sell the same approach to different, competing companies: if they all used the same approach, they can’t claim that the differences in profitability is due to the approach they were selling…

– Abbé Boulah, getting back to the question about decisions for a minute: I know we left the decision modes up for adaptation to the situation, — so as to not fall into the trap of designing a grand unified system for this discourse project, perhaps? But Isn’t that leaving the door open for another big problem — one of those grand challenges all humanity must come to grips with?

– What challenges are you talking about, again?

– Sorry Renfroe. Bog-Hubert was worrying about all the global crises threatening humanity, for which the do-gooder grand systems folks are trying to develop their ultimate system remedy. You know: Climate change, dwindling resources like food, energy, water to sustain a growing world population, conflicts and wars fought with evermore destructive weapons that threaten the survival even of the winners, the financial system booms and busts, inequality of wealth and income, health care and education.

– Oh okay. So which one of those were you talking about — for which the discourse decision provisions were leaving the door open?

– Sorry, I didn’t list that one in my examples. It’s the question of power, and how to control it. It’s one of those problems for which we need the discourse platform; and of course the way we will deal with it will affect the design of the discourse system itself.

– Yeah, yeah, the old systems rule, everything is related to and affects everything else. So? We can’t design the discourse before we solve the power problem? Sounds like a dinosaur-size chicken-and-egg problem.

– Right, Sophie: it just goes to show how wicked these issues are. But let me explain why the design of the discourse system may have some interesting ‘collateral benefit’ for the power conundrum.

– What’s the problem with power, anyway, specifically? We all want some, the communities at all sizes need power to get things done, it’s like anything, getting too much of a good thing is going to be bad for you… It’s reality, no?

– Well, let me try to explain. Yes, you are right: we all want power. To pursue our happiness — at our lowly common folks’ level we call it ’empowerment’ when we don’t have enough of it. You might consider it a kind of human right. We also need power in society: even in an ideal hypothetical society where all community decisions lead to agreements we all supported in that glorious collective discourse platform we are designing — and all are supposed to adhere to. Even there, some people might want to do things for their own greater benefit, in violation of those agreements. Deliberately or inadvertently. So societies have provisions to try to prevent the potential violators from doing that — and it’s mostly done by pursuing and imposing penalties and sanctions on the bad guys who did it. The predominant tool for that has been the set of institutions we call law enforcement and judicial. In order to do its job effectively, it must have more power that any would-be violator, right?

– Now that you point it out, oh boy; you’re right.

– Yes. It explains the escalation in arsenals and budgets on all sides. Now we know that power itself is, to put it bluntly, addictive. The powerful want more and more of it. Maybe that’s because many forms of power involve getting others to do what the powerful want them to do, but those others don’t, because they don’t get to do what they want to do, and there’s resistance, resentment. Which must be controlled by more power. And there’s a powerful temptation to break the rules, because do you really have power if you have to abide by laws and rules — even if you made those rules yourself? The Caligula syndrome. You’re not really ‘free’ unless you can do things that violate all society’s rules and laws, even laws of logic and reason? Let’s see who has power: I’ll make my horse a consul, so there.

– Okay, but haven’t we — human societies — developed some viable means of controlling power? Time limits for power-wielding office holders, elections, impeachment, balance of legislature, executive, and judicial branches of government, corruption laws…?

– Right. And some have been reasonably effective. But there are worrisome signs that those provisions are reaching the limits of their effectiveness. We can suspect some of the reasons for that — for example, that non-government entities — to which those governmental power constraints do not apply — are using their economic power to control governments.

– You mean: buying governments?

– I don’t want to speculate here — but doesn’t it sometimes look like it’s possible…? Or that it’s actually happening? But that aside: now that we are reaching a global situation where many are talking about some world government — what if that government were to be taken over by non-government entities? Already, huge corporations are operating across national borders almost as if they didn’t exist; international crime syndicates have always done that, as well as religions. It took a long time in the western world to get governments separated from the church. But the real danger is — whoever is holding the global power — that by the logic of having to be more powerful than any would-be violator of its agreements, treaties, laws — there can be no more powerful entity to keep a global government or power from playing a little loosely with this duty of adhering to the laws. Or to any agreement we may have laboriously argued our way to adopt in our global discourse forum. Will the global government be immune to the temptations of power?

– Your contribution to this discourse is getting kind of depressing here, Abbé Boulah. Any ideas what to do about that?

– You mean shut up? Sure, let’s all join the global ostrich community. Or do you actually expect lil’ ol’ me to have the answer to this conundrum that nobody really wants to discuss, as far as I can see?

– Well, I was hoping you’d have some answers…

– Coming to think of it: Haven’t we, with the help of Vodçek’s lubrications in this great Fog Island Tavern, developed some tentative, crazy ideas that may at least trigger some discussion and shake up better solutions? You may have forgotten or lost them out of sight in that fog that gave it its name.

– Come on. Quit beating around the bush and remind us!

– Okay, okay. One concept was the notion of sanctions for agreement violations that don’t require an ‘enforcement’ agency equipped with the ever-growing and ever-escalating force armament, requiring impressive ‘prosecution’ first in catching the perps and then to run them through the judicial system, resulting in high costs and then enforced penalties and punishment. Instead, to develop provisions for ‘sanctions’ that are automatically triggered by the very attempt of violation, and thereby prevent the violation before it begins.

– I remember now. We didn’t get very far with specific implementation ideas though.

– Right: though we have some promising technologies for low-grade violations, it is an idea that needs discussion, research and development. Is anybody doing that in a systematic, sustained way? Put it on the list: it’s one of the topics that should be on the discourse agenda.

– Wasn’t there also something about making power holders pay for decisions? And using some kind of credit points from the discourse and argument evaluation as the currency for that?

– Good point, Vodçek! Are you keeping a record of all the great ideas we are tossing about at your counter?

– No, it might be a good idea. But that one just stuck in my mind because it sounded so crazy.

– What in three twisters name are you guys talking about?

– Ah Sophie, you must have missed some episodes of this embryonic global tavern discourse.

– Come on, lose the fancy obscurantist talk, just explain that crazy idea Vodçek was mentioning.

– Ouch, ‘obscurantist’ — that hurts, I’ll have to treat my wounds with some Zinfandel, if Vodçek has some at hand. Bog-Hubert, do you have a clearer memory about that crazy idea?

– Well, we talked about contributions to the discourse. We wanted to encourage, invite people to contribute their ideas and concerns, on the one hand, but keep that flow of posts from getting overwhelmed by repetition. So what if there was a system giving every contributor some ‘civic credit’ points for every idea, every argument. But only the first one with the substantially same content — even if expressed in different words. That also would have the effect of getting those contributions fast — since only the first one would get the credit.

– Good idea — that would cut down of some of the volume … But what does it have to do with the power problem?

– Hold on a minute, Sophie — there’s an intermediate step we have to fill in first. It’s the argument evaluation. Some of those are very plausible, others turn out to be just blah or mistaken, or even distracting. Since these information bits and arguments are evaluated by the participants in order to develop the decision support ‘plausibility’ measure, we could use those assessments to adjust the basic contribution credit points. Upward for plausible, good and significant items, downward for worthless ones. Those revised credit points could be recorded in a ‘civic credit account’ for each participant. Now that credit can be an added criterion for electing or assigning people to power positions — you know, people who have to make fast decisions for matters that can’t wait for the outcome of lengthy and thorough discussions. They will still be needed, right? We didn’t mention those when we were talking about controlling power a while ago.

– Shucks, and here I started dreaming that we could get rid of those in our grand new system, and all go fishing… or celebrating her in the tavern?

– So sorry. But the connection to the power problem was the idea we had here some long November night, that we’d have people pay for each of those power decisions. If power is something like a human need, it’s like food and shelter and movies — we are expected to pay for it — why not for the power to make power decisions? And the credit account would be the currency for doing that. If you’ve used up your credits, guv, and there aren’t any folks willing to transfer some of their hard-earned credits to you for making those decisions on our behalf, the jig is up, back to the discussion earning more credits. Like the automatically triggered sanctions for agreement violations, it’s another partial approach for controlling power. If we are going to have any serious global agreements or ‘system’, — a kind of global government — aren’t these some really urgent issues we need to start talking about? Eh, Bog-hubert?

– Yes, that was why I wasn’t so happy about all those grand new systems proposals — there isn’t much about such issues in those glorious schemes, as far as I can see.

– So have we learned anything from this palaver, are we ready for some conclusions, however preliminary?

– Well there are a few things we could throw out as ‘best of current misconceptions’ Like:

* The ‘grand new unified system’ idea is a rather questionable one;

* Even if we thought it was needed — and arguably, some aspects are; — but we don’t really know enough to do it right yet; and there is not enough agreement about that; so

* We need more research and experiments with different ideas — small local initiatives to gain experience with what works and what doesn’t work; and feed the results into

* A global discourse for which we first need a much improved platform with an integrated support system including extracting the essential core of contributions; better display and mapping, argument evaluation, and a mechanism for linking decisions to the merit of those arguments and contributions. And

* Using some of our collateral discourse ideas for better control of power, especially the control of the power that will have to ensure adherence to global unified decisions and agreements.

* So the first global agreement we need is the design of the global discourse platform in which we can discuss whether a grand new system is needed and what it should be like.

– Well — how do we get people to start thinking and talking about those things?

– Put it on the list…

– Hey: what list? Did you forget where you are? And that this entire discussion is as fictional and hypothetical as the entire mythical Fog Island Tavern and its suspicious customers?