Part of a series of issues to clarify the role of deliberative evaluation in the planning and policy-making process. Thorbjørn Mann, February 2020.

The necessity of information technology assistance

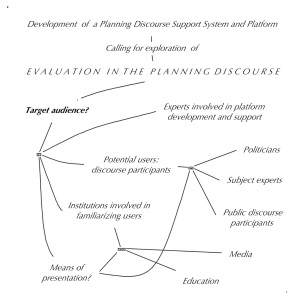

A planning discourse support platform aiming at accommodating projects that cannot be handled by small F2F ‘teams’ or deliberation bodies, must use current (or yet-to-be developed) advanced information technology, if only just to handle communication. The examination of evaluation tasks in such large project discourse, so far, also has shown that serious, thorough deliberation and evaluation can become so complex that information technology assistance for many tasks will seem unavoidable, whether in form of simple data management or more sophisticated ‘artificial intelligence‘.

So the question arises what role advanced Artificial or Augmented Intelligence tools might play in such a platform. A first cursory examination will begin by surveying the simpler data management (‘house-keeping’) aspects that have no direct bearing on actual ‘intelligence’ or ‘reasoning’ and evaluation in planning thinking, and then exploring possible expansion of the material being assembled and sorted, into the intelligence assistance realm. It will be important to remain alert to the concern of where the line between assistance to human reasoning and substituting machine calculation results for human judgment should be drawn.

‘House-keeping’ tasks

a. File maintenance. A first ‘simple’ data management task will of course be to gather and store the contributions to the discourse, for record-keeping, retrieval and reference. This will apply to all entries, in their ‘verbatim‘ form, most of which will be in conversational language. They may be stored in simple chronological order as they are entered, with date and author information. A separate file will keep track of authors and cross-reference them with entries and other actions. A log of activities may also be needed.

b. ‘Ordered’, or ‘formatted’ files. For a meaningfully orchestrated evaluation in the discourse, it will be necessary to check for and eliminate duplication of essential the same information, to sort the entries, for example according to issues, proposals, arguments, factual information, — perhaps already in some formatted manner — and to keep the resulting files updated. This may already involve some formatting of the content of ‘verbatim’ entries.

c. Preparation of displays, for overview. This will involve displays of ‘candidates’ for

decision, the resulting agenda of accepted candidates; ‘issue maps’ of the evolving discussion, evaluation and decision results and statistics.

d. Preparation of evaluation worksheets.

e. Tabulating, aggregating evaluation results for statistics and displays.

‘Analysis’ tasks, examples

f. Translation. Verbatim entries submitted in different languages and their formatted ‘content’ will have to be translated into the languages of all participants. Also, entries expressed in ‘discipline jargon’ will have to be translated into conversational language.

g. Entries will have to be checked for duplication of essential identical content, expressed in different words (to avoid counting the same content twice in evaluation procedures).

h. Standard information search (‘googling’) for available pertinent information already

documented by existing research, data bases, case studies etc. This will require the selection of search terms, and the assessment of relevance of found items, then entered into as separate section of the ‘verbatim’ file.

i. Entered items (verbal contributions and researched material) will have to be formatted for evaluation; arguments with unstated (‘taken for granted’) premises must be completed with all premises stated explicitly; evaluation aspects, sub-aspects etc must be ordered into coherent ‘aspect trees’. (Optional: Information claims found in searches may be combined to form ‘new’ arguments that have not been made by human participants).

j. Identifying argument patterns (inference rules) of arguments, and checked (to alert participants for validity problems and contradictions)

k. Normalization of weight assignments, aggregation of judgments and arguments and display if different aggregation result (different aggregation functions) as well as their effect on different decision criteria will have to be prepared and displayed.

l. More sophisticated support examples would be the development of systems models of the ‘system’ at hand, (for example, constructing cause-effect connections and loops for the factual-instrumental premises in arguments) to predict performance of proposed solutions, to simulate the behavior of the resulting system in its environment over time.

The boundary between human and machine judgments

It should be clear from preceding sections that general algorithms should not be used to generate evaluative judgments (unless there are criteria expressed in regulations, laws, or norms, to expressly substitute for human judgment.) Any calculated statistics of participant judgments should be clearly identified as ‘statistics’ of individuals’ judgments, not as ‘group judgments’. The boundary issue may be illustrated with the examination of the idea of complete ‘objectification’ or explanation of a person’s basis of judgment, with the ‘formal evaluation’ process explained in that segment. Complete description of judgment basis would require description of criterion functions for all aspect judgments, the weighting of all aspects and sub-aspects etc., and the estimates of plausibility (probability) for a plan to meet the performance expectations involved. This would allow a person A to make judgments on behalf of another person B, while not necessarily sharing B’s basis of judgment. Imagining a computer doing the same thing is meaningful only if all those values of B’s judgment basis can be given to the computer. The judgments would then be ‘deliberated’ and fully explained (not necessarily justified or mandatory for all to share).

In practice, doing that even for another person is too cumbersome to be realistic. People usually shortcut such complete objectification, making decisions with ‘offhand’ intuitive judgments — that they do not or cannot explain. That step cannot be performed by a machine, by definition: the machine must base its simulation of our judgment basis on some explanation. (Admittedly, It could be simulating the human equivalent of tossing a coin: randomly, though most humans would resent describing their intuitive judgments to be called ‘random’). And vague reference is usually made to ‘common sense’ or otherwise societally accepted values, obscuring and sidestepping the problem of dealing with the reality of significantly different values and opinions.

Where would the machine get the information for making such judgments if not from a human? Any algorithm for this would be written by a human programmer, including the specifics for obtaining the ‘factual’ information needed to develop even the most crude criterion function. A common AI argument would be that the machine can be designed to observe (gather the needed factual information) and ‘learn’ to assemble a basis of judgment, for measurable and predictable objectives such as ‘growth’ or stability (survival) of the system. The trouble is that the ‘facts’ involved in evaluating the performance and advisability of plans are not ‘facts’ at all: They are estimates, predictions of future facts, so they cannot be ‘observed’ but must be extrapolated from past observations by means of some program. And we can deceive ourselves to accept information about the desirability of ‘ought’ or ‘goodness aspects of a plan as ‘factual’ data only by looking at statistics, (also extrapolated into the future) or legal requirements — that must have been adopted by some human agent or agency.

To be sure: these observations are not intended to dismiss the usefulness of AI (that should be called augmented intelligence) for the planning discourse. They are trying to call attention to the question of where to draw the boundary between human and machine ‘judgment’. Ignoring this issue can easily lead to development of processes in which machine ‘judgment’ — presented to the public as non-partisan, ‘objective’, and therefore more ‘correct’ than human decisions, but inevitably programmed to represent some party’s intentions and values — can become sources of serious mistakes, and tools of oppression. This brief sketch can only serve as encouragement to more thorough discussion.