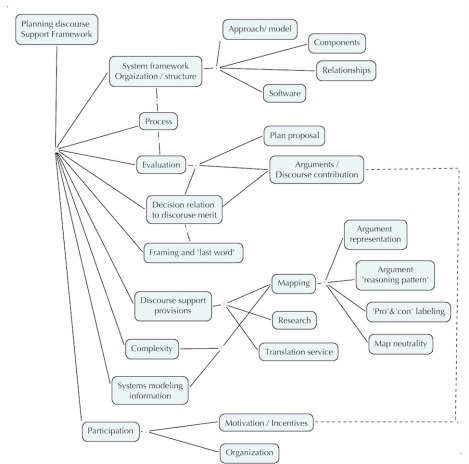

Re-examining various efforts and proposals on discourse support over time, I have tried to identify and address some key issues or problems that require attention and rethinking. Briefly, the list of issues includes the following (in no particular order of importance):

• The question of the appropriate Conceptual Framework for the discourse support system;

• The preparation and use of discourse, issue and argument maps, ncluding the choice of map ‘elements’ (questions, issues, arguments, concepts or topics…);

• The design of the organizational framework: the ‘platform’;

• The Software problem: Specifications for discourse support software;

• Questions of appropriate process;

• The role and design of discourse mapping;

• The aspect of distributed information;

• The problem of complexity of information (complexity of linear verbal or written discussion, complex reports, systems model information);

• The role of experts;

• Negative associations with the term ‘argument’;

• The problem of ‘framing’ the discourse;

• Inappropriate focus on insignificant issues;

• The role of media;

• Appropriate Discussion representation;

• Incentives / motivation for participation (‘Voter apathy’)

• The ‘familiar’ (comfortable?) linear format of discussions versus the need (?) for structuring discourse contributions;

• The need for overview of the number of issues / aspects of the problem and their relationships;

• The effect of ‘last word’ contributions (e.g. speeches) on collective decisions; or mere ‘rhetorical brilliance’;

• Linking discussion merit / argument merit with eventual decisions;

• The issue of maps ‘taking sides’;

• The problem of evaluation: of proposals, arguments, discussion contributions;

• The role of ‘systems models’ information in common (verbal, linear, including ‘argumentative’) discourse

• The question of argument reconstruction.

• The appropriate formalization or condensation needed for concise map representation;

• Differences between requirements for e.g. ‘argument maps’ as used in e.g. law or science versus planning;

• The deliberate or inadvertent ‘authoritative’ effect of e.g. argument representation as ‘valid’; (i.e. the extent of evaluative content of maps);

• The question of appropriate sequence of map generation and updating;

• The question of representation of qualifiers in evaluation forms.

In previous work on the structure and evaluation of ‘planning arguments’ within the overall framework of the ‘Argumentative Model of Planning’ (as proposed by Rittel), I have been making various assumptions with regard to these questions — assumptions differing from those made in other studies and proposed discourse support tools. Such assumptions, for example regarding the conceptual framework, as manifested in the choice of vocabulary, — adopted as a mostly unquestioned matter of course in my proposals as well as in other’s work, — have significant implications on the development of such discourse support tools. They therefore should be raised as explicit issues for discussion and re-examination.

A first step in such a re-examination might begin with an attempt to explicitly state my current position, for discussion. This position is the result, to date, of experience with my own ideas as well as the study of others’ proposals. Not all of the issues listed above will be addressed in the following. Some position items still are, in my mind, more ‘questions’ than firm convictions, but I will try to state them as ‘provocatively’ as possible, for discussion and questioning.

1 The development of a global support framework for the discussion of global planning and policy agreements, based on wide participation and assessment of concerns, is a matter of increasingly critical concern; it should be pursued with high priority.

While no such system can be expected to achieve definitive universal validity and acceptance, and therefore many different efforts for further development of alternative approaches should be encouraged, there is a clear need for some global agreements and decisions that must be based on wide participation as well as thorough evaluation of concerns and information (evidence).

The design of a global framework will not be structurally different from the design of such systems for smaller entities, e.g. local governments. The differences would be mainly ones of scale. Therefore, experimental systems can be developed and tested at smaller scales to gain sufficient experience before engaging in the investments that will be needed for a global framework. By the same token, global systems for initially very narrow topics would serve the same purpose of incremental development and implementation.

2 The design of such a framework must be based on — and accommodate — currently familiar and comfortable habits and practices of collective discussion.

While there are analytical techniques and tools with plausible claims of greater effectiveness, ability to deal with the amount and complexity of data etc., the use of these tools in discourse situations with wide participation of people of different educational achievement levels would either be prohibitive of wide participation, or require implausibly massive information/education programs for which precisely the needed tools for reaching agreement on the selection of method / approach (among the many competing candidates) are currently not available.

3 Even with the growing use of new information technology tools, the currently most familiar and comfortable discourse pattern seems to be that of the traditional ‘linear discussion’ (sequential exchange of questions and answers or arguments) — the pattern that has been developed in e.g. the parliamentary tradition, the agreement of giving all parties a chance to speak, air their concerns, their pros and cons to proposed collective actions, before making a decision.

This form of discourse, originally based on the sequential exchange of verbal contributions, is of course complemented and represented by written documents, reports, books, and communications.

4 A first significant attempt to enhance the ‘parliamentary’ tradition with systematic information system, procedural and technology support was Rittel’s ‘Argumentative Model of Planning’. It is still a main candidate for the common framework.

Rittel’s main argument for the general acceptance of this model was the insight that its basic, general conceptual framework of ‘questions’, ‘issues’ (controversial questions), ‘answers’, and ‘arguments’ could in principle accommodate the content of any other framework or approach, and thus become a bridge or common forum for planning at all levels. This still seems to be a valid claim not matched by any other theoretical approach.

5 However, there are sufficiently worrisome ‘negative associations’ with the term ‘argument’ of Rittel’s model to suggest at least a different label and selection of more neutral key concepts and terms for the general framework

The main options are to only refer to ‘questions’ and ‘responses’ and ‘claims’, and to avoid ‘argument’ as well as the concepts of ‘pro’s and ‘cons’ — arguments in favor and opposed to plan proposals or other propositions.

Argumentation can be seen as the mutually cooperative (positive) effort of discussion participants to point out premises that support their positions, but that also are already believed to true or plausible by the ‘opponent‘, (or will be accepted by the opponent upon presentation of evidence or further arguments). But the more common, apparently persistent view is that of argumentation as a ‘nasty’, adversarial, combative ‘win-lose’ endeavor. While undoubtedly discourse by ay other label will produce arguments, pros and cons etc., the question is whether these should be represented as such in support tools, or in a more neutral vocabulary.

Experiments should be carried out with representations of discourse contributions — in overview maps and evaluation forms — as ‘questions’ and ‘answers’.

6 Any re-formatting, reconstruction, condensing of discussion contributions carries the danger of changing the meaning of an entry as intended by its author.

Regardless of the choice of such formatting — which should be the subject of discussion — the framework must preserve all original entries in their ‘verbatim’ form for reference and clarification as needed. Ideally, any reformatting of an entry should be checked with its author to ensure that it represents its intended meaning. (Unfortunately, this is not possible for entries whose authors cannot be reached, e.g. because they are dead.)

7 The framework should provide for translation services not only for translation between natural languages, but also from specialized discipline ‘jargon’ entries to natural language.

8 While researchers in several disciplines are carrying out significant and useful efforts towards the development of discourse support tools, and some of these efforts seem to claim to produce universally applicable tools, such claims are overly optimistic.

The requirements for different disciplines are different, and lead to different solutions that cannot comfortably be transferred to other realms. Specifically, the differences between scientific, legal, and planning reasoning are calling for quite different approaches. and discourse support systems. However, they are not independent: the planning discourse contains premises from all these realms that must be supported with the tools pertinent to those differences. The diagram suggests how different discourse and argument systems are related to planning:

(Sorry, diagram will be added later)

9 Analysis and problem-solving approaches can be distinguished according to the criteria they recommend as the warrant for solution decisions:

– Voting results (government, management decision systems, supported by experts);

– ‘Backwards-looking’ criteria: ‘Root cause’ (Root cause analysis, ‘Necessary conditions, contributing factors (‘Systematic Doubt’ analysis), historical data (Systems models);

– ‘Process/Approach’ criteria (“the ‘right’ approach guarantees the solution”);

solutions legitimized by participation vote or authority position; or argument merit;

– ‘Forward-looking’ criteria: Expected result performance, Benefit-Cost Ratio, simulated performance of selected variables over time, or stability of the system, etc.

It should be clear that the framework must accommodate all these approaches, or preferably, be based on an approach that could integrate all these perspectives, as applicable to context and characteristics of the problem. There is, to my knowledge, currently no approach matching this expectation, though some are claiming to do so (e.g. ‘Multi-level Systems Analysis’, which however is looking at only approaches deemed to fit within the realm of ‘Systems Thinking).

10 While the basic components of the overall framework should be as few, general, and simple as possible, — for example ‘topic’, ‘question’ and ‘claim’ or ‘response’, — actual contributions in real discussions can be lengthy and complex, and must be accommodated as such (in ‘verbatim’ reference files). However, for the purposes of overview by means of visual relationship mapping, or systematic evaluation, some form of condensed formatting or formalization will be necessary.

The needed provisions for overview mapping and evaluation are slightly different, but should be as similar as possible for the sake of simplicity.

11 Provisions for mapping:

a. Different detail levels of discourse maps should be distinguished: ‘Topic maps’, ‘Issue maps’ (or ‘question maps’), and ‘argument maps’ or ‘reasoning maps’.

– Topic maps merely show the general topics or concepts and their relationship as linked by discussion entries. Topics are conceptually linked (simple line) if they are connected by a relationship claim in a discussion entry.

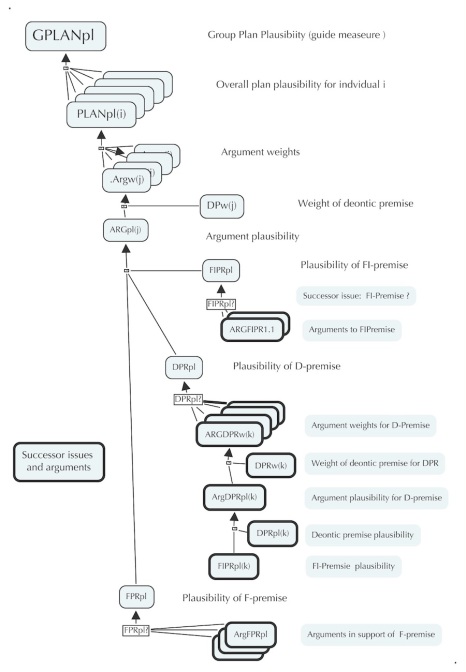

– Issue or question maps show the relationships between specific questions raised about topics. Questions can be identified by type: e.g. factual, deontic, explanatory, instrumental questions. There are two main kinds of relationships: one is the ‘topic family’ relation (all questions raised about a specific topic); the other is the relationship of a question (a ‘successor’ question) having been raised as a result of challenging or query for clarification of an element (premise) of another (‘predecessor‘) question.

– Argument or reasoning maps show the individual claims (premises) making up an answer or argument about an issue (question), and the questions or issues having been raised as a result of questioning any such element (e.g. challenging or clarifying, calling for additional support for an argument premise.

b. Reasoning maps (argument maps) should show all the claims making up an argument, including claims left not expressed in the original ‘verbatim’ entry as assumed to be ‘taken for granted’ and understood by the audience.

Reasoning maps aiming at encouraging critical examination and thinking about a controversial subject might show ‘potential’ questions (for example the entire ‘family of issues for a topic) that could or should be raised about an answer or argument. These might be shown in gray or faint shades, or a different color from actually raised questions.

c. Reasoning maps should not identify answers or arguments as ‘pro’ and ‘con’ a proposal or position (unless it is made very clear that these are only the author’s intended function.)

The reason is that other participants might disagree with one or several of the premises of an intended ‘pro’ argument, in which case the set of premises (not with the respective participant’s negation) can constitute a ‘con’ argument — but the map showing it as ‘pro’ would in fact be ‘taking sides’ in the assessment. This would violate the principle of the map serving as a neutral, ‘impartial’ support tool.

d. For the same reason, reasoning maps should not attempt to identify and state the reasoning pattern (e.g. ‘modus ponens’ or modus tollens’ etc.) of the argument. Nor should they ‘reconstruct’ arguments into such (presumably more ‘logical’, even ‘deductively valid’) forms.

Again, if in a participant’s opinion, one of the premises of such an argument should be negated, the pattern (reasoning rule) of the set of claims will become a different one. Showing the pattern as the originally intended one by the author, (however justified by its inherent nature and validity of premises it may seem to map preparers), the map would inadvertently or deliberately be ‘taking sides’ in the assessment of the argument.

e. Topic, issue and reasoning maps should link to the respective elements in the verbatim and any formalized records of the discussion, including to source documents, and illustrations (pictures, diagrams, tables).

d. The ‘rich image’ fashion (fad?) of adding icons and symbols (thumbs up or down, plus or minus signs) or other decorative features to the maps — moving bubbles, background imagery, etc. serve as distracting elements more than as well-intended user-friendly devices, and should be avoided.

12 Current discourse-based decision approaches exhibit a significant shortcoming in that there is no clear, transparent, visible link between the ‘merit’ of discussion contributions and the decision.

Voting blatantly permits disregarding discussion results entirely. Other approaches (e.g. Benefit-Cost Analysis, or systems modeling) claim to address all concerns voiced e.g. in preparatory surveys, but disregard any differences of opinion about the assumptions entering the analysis. (For example: some entities in society would consider the ‘cost’ of government project expenditures as ‘benefits’ if they lead to profits for those entities (e.g. industries) from government contracts).

The proposed expansion of the Argumentative Model with Argument Evaluation (TM 2010) provides an explicit link between the merit of arguments (as evaluated by discourse participants) and the decision, in the form of measures of plan proposal plausibility. This approach should be integrated into an approach dropping the ‘argumentative‘ label, even though it requires explicit or implicit evaluation of argument premises.

13 Provisions for evaluation.

In discussion-based planning processes, three main evaluation tasks should be distinguished: the comparative assessment of the merit of alternative plan proposals (if more than one); the evaluation of one plan proposal or proposition, as a function of the merit of arguments; and the evaluation of the merit of single contributions, (item of information, arguments) to the discussion.

For all three, the basic principle is that evaluation judgments must be understood as subjective judgments, by individual participants, about the quality, plausibility, goodness, validity desirability etc. While traditional assessments e.g. of truth of argument premises and conclusions were aiming at absolute, objective truth, the practical working assumption here is that while we all strive for such knowledge, we must acknowledge that we do not have any more than (utterly subjective) estimate judgments of it, and it is on the strength of those estimates we have to make our decisions. The discussion is a collective effort to share and hopefully improve the basis of those judgments.

The first task above is often approached by means of a ‘formal evaluation’ procedure developing ‘goodness’ or performance judgments about the quality of the plan alternatives, resulting on an overall judgment score as a function of partial judgments about the plans’ performance with respect to various aspects. sub-aspects etc. Such procedures are well documented; the discourse may be the source of the aspects, but more often, the aspects are assembled (by experts) by a different procedure.

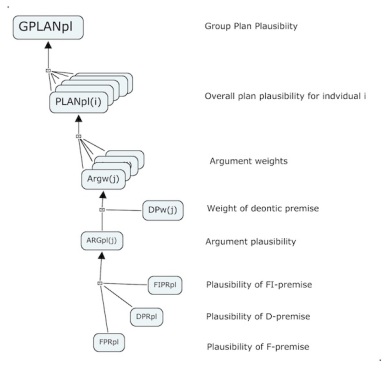

The following suggestions are exploring the approach of developing a plausibility score for a plan proposal based on the plausibility and weight assessments of the (pro and con) arguments and argument premises. (following TM 2010 with some adaptations).

a. Judgment criterion: Plausibility.

All elements to be ‘evaluated’ are assessed with the common criterion of ‘plausibility’, on an agreed-upon scale of +n (‘completely plausible’) to -n (‘completely implausible’), the midpoint score of zero meaning ‘don’t know’ or ‘neither plausible nor implausible’.

While many argument assessment approaches aim at establishing the (binary) truth or falsity of claims, ‘truth’, (not even ‘degree of certainty’ or probability about the truth of a claim), does not properly apply to deontic (ought-) claims and desirability of goals etc. The plausibility criterion or judgment type applies to all types of claims, factual, deontic, explanatory etc.

b. Weights of relative importance

Deontic claims (goals, objectives) are not equally important to people. To express these differences in importance, individuals assign ‘weight of relative importance) judgments to deontics in the arguments, on an agreed upon scale of zero to 1 such that all weights relative to an overall judgment add up to 1.

c. All premises of an argument are assigned premise plausibility judgments ppl; the deontic premises are also assigned their weight of relative importance pw.

d. The argument plausibility argpl of an argument is a function of the plausibility values of all its premises.

e. Argument weight argw is a function of argument plausibility argpl and the weight ppw of its deontic premise.

f. Individual Plan or Proposal plausibility PLANpl is a function of all argument weights.

g. ‘Group’ assessments or indicators of plan plausibility GPLANpl can be expressed as some function of all individual PLANpl scores.

However, ‘group scores’ should only be used as a decision guide, together with added consideration of degrees of disagreement (range, variance), not as a direct decision criterion. The decision may have to be taken by traditional means e.g. voting. But the correspondence or difference between deliberated plausibility scores and the final vote adds an ‘accountability’ provision: a participant having assigned a deliberated positive plausbility score for a plan but voting against it will face strong demands for explanation.

h. A potential ‘by-product’ of such an evaluation component of a collective deliberation process is the possibility of rewarding participants for discussion contributions not only with reward points for making contributions — and making such contributions speedily, (since only the ‘first’ argument making the same point will be included in the evaluation) — but modifying these contribution points with the collective assessments of their plausibility. Thus, participants will have an incentive — and be rewarded for — making plausible and meritorious contributions.

14 The process for deliberative planning discourse with evaluation of arguments and other discourse contributions will be somewhat different from current forms of participatory planning, especially if much or all of it is to be carried out online.

The main provisions for the design of the process pose no great problems, and small experimental projects can be carried out with current tools ‘by hand’ with human facilitators and support staff using currently available software packages. But for larger applications adequate integrated software tools will first have to be developed.

15 The development of ‘civic merit accounts’ based on the evaluated contributions to public deliberation projects may help the problem of citizen reluctance (often referred to as the problem of ‘voter apathy’) to participate in such discourse.

However, such rewards will only be effective incentives if they can become a fungible ‘currency’ for other exchanges in society. One possibility is to use the built-up account of such ‘civic merit points’ as one part of qualification for public office — positions of power to make decisions that do not need or cannot wait for lengthy public deliberation. At the same time, the legitimization for power decisions must be ‘paid for’ with appropriate sums of credit points — a much-needed additional form of control of power.

16 An important, yet unresolved ‘open question’ is the role of complex ‘systems modeling’ information in any form of argumentative planning discourse with the kind of evaluation sketched above.

Just as disagreement and argumentation about model assumptions are currently not adequately accommodated in systems models, the information of complex systems models and e.g. simulation results is difficult to present in coherent form in traditional arguments, and almost impossible to represent in argument maps and evaluation tools. Since systems models arguably are currently the most important available tools for detailed and systematic analysis and understanding of problems and system behavior, the integration of these tools in the discourse framework for wide public participation must be seen as a task of urgent and high priority.

17 Another unresolved question regarding argument evaluation (and perhaps also mapping) is the role of statement qualifiers.

Whether arguments that are stated with qualifiers (‘possibly’, ‘perhaps’; ‘tend to’ etc.) in the original ‘verbatim’ version should show such qualifiers in the statements (premises) to be evaluated. Arguably, qualifiers can be seen as statements about how an unqualified, categorical claim should be evaluated; the proponent of a claim qualified with a ‘possible’ does not ask for a complete 100% plausibility score. This means that the qualifier belongs to a separate argument about how the main categorical claim should be assessed, and thus should not be included in the ‘first-level’ argument to be evaluated. The problem is that the qualified claim can be evaluated — as qualified — as quite, even 100% plausible — but that plausibility can (in the aggregation function) be counted as 100% for the unqualified claim. Unless the author can be persuaded to add an actual suggested plausibility value in lieu of the verbal qualifier, one that other evaluators can view and perhaps modify according to their own judgment (unlikely and probably impractical), it would seem better to just enter unqualified claims in the evaluation forms, even though this may be seen as misrepresenting the author’s real intended meaning.

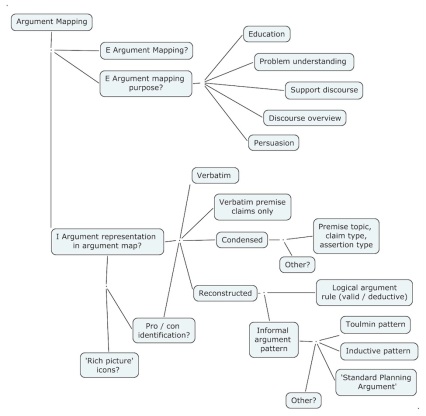

18 Examples of topic, issue, and argument maps according to the preceding suggestions.

a. A ‘topic map’ of the main topics addressed in this article:

Map of topics discussed

b. An issue map for one of the topics:

Argument mapping issues

c. A map of the ‘first level’ arguments in a planning discourse: the overall plan plausibility as a function of plausibility and weight assessments of the planning arguments (pro and con) that were raised about the plan.

The overall hierarchy of plan plausibility judgments

d. The preceding diagram with ‘successor’ issues and respective arguments added.

Hierarchy map of argument evaluation judgments, with successor issues

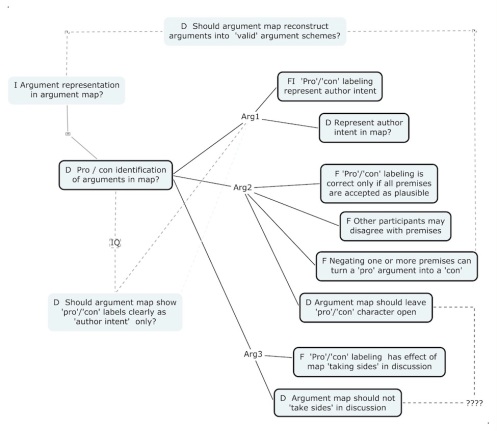

e. An example of a map of first level arguments for a selected mapping issues

Argument map for mapping issue ‘Should argument map show ‘pro’ and ‘con’ labels?

References

Mann, T. (2010) “The Structure and Evaluation of Planning Arguments” Informal Logic, Dec. 2010.

Rittel, H. (1972) “On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of the ‘First and Second Generations’.” BedriftsØkonomen. #8, 1972.

– (1977) “Structure and Usefulness of Planning Information Systems”, Working Paper S-77-8, Institut für Grundlagen der Planung, Universität Stuttgart.

– (1980) “APIS: A Concept for an Argumentative Planning Information System’. Working Paper No. 324. Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California.

– (1989) “Issue-Based Information Systems for Design”. Working Paper No. 492. Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California.

—-